Hartford Public Schools

Southwest School The original small building of SOUTHWEST SCHOOL had been part of the Hartford landscape since being constructed in1844 on White Street. The building was made of wood and only had one room, which was heated by a large stove. Throughout the century, the schoolhouse went through a long period of vacancy until the late 1890s. A rise in the population of the district allowed the school to reopen and accommodate the growing number of students. Even at that time it was still too small, and within a few years plans to build a new schoolhouse were underway. A new school was built in 1900, designed by Isaac Almarin Allen, Jr. In 1954, the Southwest School was renamed the Eleanor B. Kennelly School. (Photo: Hartford Public Schools 1899. Courtesy of the Tomas J. Nenortas Collection).

The original small building of SOUTHWEST SCHOOL had been part of the Hartford landscape since being constructed in1844 on White Street. The building was made of wood and only had one room, which was heated by a large stove. Throughout the century, the schoolhouse went through a long period of vacancy until the late 1890s. A rise in the population of the district allowed the school to reopen and accommodate the growing number of students. Even at that time it was still too small, and within a few years plans to build a new schoolhouse were underway. A new school was built in 1900, designed by Isaac Almarin Allen, Jr. In 1954, the Southwest School was renamed the Eleanor B. Kennelly School. (Photo: Hartford Public Schools 1899. Courtesy of the Tomas J. Nenortas Collection).

In the early years of the NORTHWEST SCHOOL, the boys of the schoolhouse were known for their “tough” reputation. It was so hard to keep them behaving properly that the teachers were enforced to use corporal punishment, and it was not uncommon for students to receive expulsion. The author of Public Schools of Hartford attended the school himself, and wrote, “That tough old school of shabby memory developed whatever grit and determination the boy had in him, as inevitably as it broadened his knowledge of numbers, language, and the surface of the earth…”[1] Unfortunately, many parents in the district were not as optimistic about the schoolhouse.

In the early years of the NORTHWEST SCHOOL, the boys of the schoolhouse were known for their “tough” reputation. It was so hard to keep them behaving properly that the teachers were enforced to use corporal punishment, and it was not uncommon for students to receive expulsion. The author of Public Schools of Hartford attended the school himself, and wrote, “That tough old school of shabby memory developed whatever grit and determination the boy had in him, as inevitably as it broadened his knowledge of numbers, language, and the surface of the earth…”[1] Unfortunately, many parents in the district were not as optimistic about the schoolhouse.

It was not until the demolition of the schoolhouse and the building of a new one in 1870, on Albany Avenue, that the reputation was lessened. The new building was brick, and comprised of only two rooms. It supplied the school with enough space for a little over ten years. By the middle of the 1880s, overcrowding required the school to add another addition. A four room addition was added in 1885, which promised enough space for the next fifteen years.[1]

Over the next decade, the student body increased dramatically. The large increase could be traced back to two factors; one, the increase of the population in the district, and two, being the great improvement of the school’s reputation. This great improvement began after the development of the music program, directed by Professor F. Zuchtmann, who in less than two years made the Northwest students known across the state as “remarkable singers.”[3] Zuchtmann was a highly respected man, and many thought of him as “one of the best known musicians in the country.”[4] He taught in Germany, were he was born, until 1850, when he fled to America to escape the revolutions. He briefly taught in New York and New Hampshire before settling down in Boston for twenty years. There he was associated with the Conservatory of Music, and played at Music Hall. Author of The American Music System, Zuchtmann cared deeply for the education of his pupils, and his methods were used in many cities across America.[5] He was the music director at Amherst College until the last few years before he died.

A year before the turn of the twentieth-century, a large addition was completed that expanded the school to over twice its size. It provided an additional eight classrooms, a large assembly hall, library and principal’s office to the school. It cost the district around $54,000, and was designed by architects, Hapgood & Hapgood.[6] The addition began at the northwest side of the school, and was connected by a room that was used for lunch and recess. The design of the addition was Queen Anne style, which was a very popular style during the time period. Regrettably, the addition was knocked down in 1978.[7]

~ Researched and written by Rebecca Fenerty, HPA Intern, March 2011

Footnotes

1 Public Schools of Hartford, 61.

2 Ibid, 62.

3 Ibid.

4 “Frederick Zuchtmann.” The Hartford Courant, Dec 11, 1909.

5 “Singing in Public Schools.” The Hartford Courant, Jun 12, 1895. 3.

6 “New School Addition.” The Hartford Courant, Aug 30, 1898. 8.

7 George Andrews and David Ransom, Structures and Styles: Guided Tours of Hartford Architecture, 120.

The NORTHEAST SCHOOL building was erected in 1871 at 54 Westland Street. The school was built in the Northeast School District which was established in 1833, despite the area’s long time settlement. Farmers had been home to the land many years prior to the naming of the district. The original Northeast School building consisted of three stories, containing twelve rooms, and a basement. The primary material was brick, with brownstone trimming. An influx of students meant accommodations had to be made to the original structure. The largest change was an addition completed in 1920, costing the district a massive $250,000, designed by architects Whiton & McMahon.

The NORTHEAST SCHOOL building was erected in 1871 at 54 Westland Street. The school was built in the Northeast School District which was established in 1833, despite the area’s long time settlement. Farmers had been home to the land many years prior to the naming of the district. The original Northeast School building consisted of three stories, containing twelve rooms, and a basement. The primary material was brick, with brownstone trimming. An influx of students meant accommodations had to be made to the original structure. The largest change was an addition completed in 1920, costing the district a massive $250,000, designed by architects Whiton & McMahon.

~ Researched & written by Rebecca Fenerty, HPA Intern, March 2011

The WILSON STREET SCHOOL opened in 1874, accepting around seventy five students. Wilson School was part of the Washington Street School district, and served as a branch to Washington School, which was the main school. In the early 1870s, it was decided that these two schools would be built for the district.[1] The Wilson Street School provided education for the children, in an area of the district which was nicknamed “over the rock,” that was much closer to their homes than the school on Washington Street. The original Wilson Street School consisted of four rooms; the intermediate room, two primary rooms and a kindergarten. The principle of the Washington Street School, Elizabeth J. Cairns, was also the supervisor for the Wilson School. The architect of the Wilson School is unknown, however, the transformation of the school has been documented.

The WILSON STREET SCHOOL opened in 1874, accepting around seventy five students. Wilson School was part of the Washington Street School district, and served as a branch to Washington School, which was the main school. In the early 1870s, it was decided that these two schools would be built for the district.[1] The Wilson Street School provided education for the children, in an area of the district which was nicknamed “over the rock,” that was much closer to their homes than the school on Washington Street. The original Wilson Street School consisted of four rooms; the intermediate room, two primary rooms and a kindergarten. The principle of the Washington Street School, Elizabeth J. Cairns, was also the supervisor for the Wilson School. The architect of the Wilson School is unknown, however, the transformation of the school has been documented.

The school’s original structure was a wood frame which has been replaced many years ago. In 1902, architect J.J. Dwyer drew the plans for an addition to the school. These plans included a brick wall for the rear, a tin roof, better heating, four new rooms and the renovation of the basement.[2] The brick rear is still visible today and is the side facing Hillside Avenue. It cost the district $16,000 at the time and supplied the students with much more comfortable place to learn. The students’ education was the primary and only reason of concern. The Hartford Courant contained many concerns of residents in the district who pushed for the addition of the school. Before the vote took place, Alexander Angus, who was the district chairman at the time, stated “that the addition must be built or the district could not accommodate the children.” Reverend Herman Lillenthal insisted “that the children of ‘over the rock’ should have as good an opportunity for an education as those in any other part of the district or city.” After Rev. Herman Lillenthal expressed his concerns, it is recorded, “his remarks were received with applause and the last resolution was passed unanimously.” The addition was completed in 1903, and the district was extremely pleased with its outcome.[3]

The school experienced another transformation in 1917, completely changing the entire appearance of the building. The original frame structure was removed and replaced with a brick building. The architect of the new design was Edward T. Wiley of Hartford. Not long after, in 1921, Whiton & McMahon designed the final extension. Since these alterations, the name of the school has changed as well.[4] The school was renamed the Thomas A. McDonough School in 1963. It was renamed after a former teacher and principle of the Wilson Street School, who had been part of the school since 1926 as its vice-principle. In 1931, Thomas became principle of the Hillside Avenue School, and when it combined with the Wilson Street School in 1934, he became the sole principle of the joined schools. Thomas was not just a principle, but an athletic coach for the Wilson and Washington schools. He graduated from State Teachers College and the University of Massachusetts.[5] The Thomas A. McDonough School is still standing today at 100 Wilson Street but is completely unrecognizable from its original form.[6]

~ researched by Rebecca Fenerty, HPA Intern, February 2011

- Public Schools of Hartford, 47.

- Ibid.

- “Wilson Street School.” The Hartford Courant, July 18, 1902.

- Structures and Styles, 89

- “T.J. McDonough, School Principle, To be Honored.” The Hartford Courant, January 31, 1960.

- Hartford Architecture Volume Two: South Neighborhoods, 189.

The SOUTH or WADSWORTH STREET SCHOOL, renamed the Chauncey Harris School in 1916, was completed in 1886 and located at 66 Wadsworth Street. Designed by architect George H. Gilbert (1829-1911), it was built of brick with brownstone trimmings and a slate roof. Playrooms and “water closets” were in the basement, school rooms on the 1st & 2nd floors and an assembly hall seating 1200 was located on the 3rd floor. Preservation activists rallied in vain to persuade the city to consider adaptive re-use of the building after the school was closed in 1974. It was razed in 1976 and the site used for the construction of affordable housing.

The SOUTH or WADSWORTH STREET SCHOOL, renamed the Chauncey Harris School in 1916, was completed in 1886 and located at 66 Wadsworth Street. Designed by architect George H. Gilbert (1829-1911), it was built of brick with brownstone trimmings and a slate roof. Playrooms and “water closets” were in the basement, school rooms on the 1st & 2nd floors and an assembly hall seating 1200 was located on the 3rd floor. Preservation activists rallied in vain to persuade the city to consider adaptive re-use of the building after the school was closed in 1974. It was razed in 1976 and the site used for the construction of affordable housing.

Photo: Hartford Public Schools 1899. Courtesy of the Tomas J. Nenortas Collection)

~researched by Mary A. Falvey, HPA Staff, December 2010

The BROWN SCHOOL, designed by architect George H. Gilbert (1829-1911), was completed in 1868 and located at the corner of Market and Talcott Streets in Downtown Hartford. The First School District built this Classical style building of Boston-pressed brick with Portland brownstone for the amazing sum of $200,000 to accommodate 1,200 students. The Annex (building to the left) was built in 1898 to provide room for another 500 pupils. In 1951, the original school was torn down and a 1922 addition soon after became the headquarters for the Hartford Police Department, a courthouse and the city jail.

The BROWN SCHOOL, designed by architect George H. Gilbert (1829-1911), was completed in 1868 and located at the corner of Market and Talcott Streets in Downtown Hartford. The First School District built this Classical style building of Boston-pressed brick with Portland brownstone for the amazing sum of $200,000 to accommodate 1,200 students. The Annex (building to the left) was built in 1898 to provide room for another 500 pupils. In 1951, the original school was torn down and a 1922 addition soon after became the headquarters for the Hartford Police Department, a courthouse and the city jail.

(Photo: Hartford Public Schools 1899. Courtesy of the Tomas J. Nenortas Collection)

~researched by Mary A. Falvey, HPA Staff, November 2010

Goodwin Building & Asylum Street

More about Goodwin Building & Asylum StreetAt the far right of the photograph is the clothing store of John Henry Otis at 210 Asylum Street. Otis came from a family of clothiers, and lived most of his life in Hartford. A local newspaper noted that he was “a man of peculiarly happy disposition,” who made and kept friends easily. Directly across the street from Otis’s store stands one of the most architecturally beautiful buildings in the city, the Goodwin Building, which unlike so many other structures in this view, still stands today.

In the late nineteenth century, the Rev. Francis Goodwin visited London and became enchanted by the great architecture then being constructed in that city, with interesting Queen Ann designs and the innovative use of terra cotta for ornamentation. When Goodwin returned to Hartford, he sought to make a building in his home city that evoked what he saw in Europe.

The venerable Goodwins owned a lot at the corner of Asylum and Haynes Streets, and the Reverend hired New York architects Francis Kimball and Thomas Wisedell to design his vision. Built in three sections through the 1880s and 1890s, the finished structure, named the Goodwin Building, had commercial space on the ground floor with upscale apartments above. The apartment house became a very prestigious address, and even J.P Morgan lived there from time to time when visiting the city of his birth. His room even had a large, closet-sized vault.

As a result of its groundbreaking use of Queen Anne influences and terra cotta, the Goodwin Building was unlike anything in Hartford at the time, and was rare among all American structures. The terra cotta allowed for magnificent and intricate carvings and motifs along the exterior, and the pattern of bays and windows presented a very appealing design. In contrast, the interior was much simpler, being done in the popular Arts and Crafts style.

During the mid-1980s, though, the interior was completely gutted, and by the end of the decade a 522 foot tall modern skyscraper rose from the historic terra cotta shell. This new Goodwin Building housed offices and a hotel, though the hotel closed its doors two years ago. The original Goodwin Building exterior, once one of Asylum Street’s most magnificent and noticeable structures, is now lost at the bottom of a dark canyon of surrounding skyscrapers.

(Photo: Courtesy of the Tomas J. Nenortas Collection)

~ Researched and written by Todd Jones, HPA Intern, October 2010

Retreat for the Insane

More about Retreat for the InsaneDr. Eli Todd, a very prominent doctor in the state, was the major impetus behind the hospital’s establishment. He lead a petition to secure state funds for the hospital, and upon its completion, became the Retreat’s first director. Dr. Todd was not only a leading mental health physician, but also dealt a great deal with smallpox, establishing the famous “Hospital Rock” in Farmington in the late eighteenth century. Eli Todd is buried in Hartford’s Old North Cemetery.

In 1868, the Retreat’s main hall was greatly expanded beyond its original 1823 foundation. This updated structure, designed by Calvert Vaux and Frederick C. Withers, stands mostly unaltered to this day. The campus grew through the next decade, and in 1877 famous architect George Keller designed White Hall. Also during this time period, the state of Connecticut opened a new mental health hospital in Middletown, which helped to alleviate overcrowding at the Retreat. The Hartford Retreat sought larger rooms with better ventilation to ensure the comfort of their patients

The Retreat also enjoyed expansive grounds on the campus, which provided patients with outdoor natural space. In 1862, esteemed landscape architects Frederick Law Olmsted and Jacob Weidenmann paired to design the Retreat’s grounds. Olmstead is also famous for designing New York’s Central Park, while Weidenmann planned Hartford’s Cedar Hill Cemetery; both are buried in Hartford.

In recent years, as a well-known research institution, the hospital has also partnered with Trinity College and other local organizations to form Hartford’s “Learning Corridor,” spurring educational advancement for the entire region. As one of the nation’s oldest hospitals, the Retreat has helped mental health patients for over 180 years, and as it is known today, the Institute of Living is likely to continue that noble mission for decades to come. (Photo: Sunlight Pictures, 1892, courtesy of the Tomas J. Nenortas Collection)

~ Researched and written by Todd Jones, HPA Intern, October 2010

Foot Guard Hall

More about Foot Guard HallAfter designer and builder John C. Mead completed the building in 1888, it was billed as the largest social hall in the state, and the Hartford Courant predicted it “is likely to become in the future an exceedingly popular resort for the better class of concerts, lectures, receptions, fairs, and even for dramatic entertainments.” But then came the far-larger State Armory in 1909, and the Bushnell in 1930, and then the Civic Center, mere blocks away.

Through the years, Foot Guard Hall continued to become smaller and smaller. Yet, it still persevered, and hosted a number of famous entertainers, including John Philip Sousa, Sophie Tucker, Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie, Harry James, and Benny Goodman. The opening of the Bushnell in particular, helped push the big entertainers away from Foot Guard Hall. Boxing and wrestling matches, though, became a big draw, and Hartford’s own Willie Pep fought there.

The Hall itself was built as, and continues to be, the home of the First Company Governor’s Foot Guard, hence the name Foot Guard Hall. The historic organization formed in 1771 as the official bodyguard of the Governor. It has traveled abroad, marched in state inaugurations, and presidential funerals. Though the State Capitol is no longer in view from the Hall, the Governor’s Foot Guard continues its original role as a ceremonial unit. The organization uses the building, with its large hall, storage areas, and office-space, to drill, train, and converse. In recent years, a former rifle-range room was transformed into a museum of the Foot Guard, open to the public.

The structure itself is located at 159 High Street, and is five stories tall. The exterior is made of wonderful red brick, and the building’s most distinctive feature is a large, central pyramidal roof above the front entrance. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, that detail would have nicely complimented the similar pyramid which used to top the famous Cheney Block on Main Street, and Foot Guard Hall appropriately has many Richardsonian influences in its creative design. (Photo: Courtesy of the Tomas J. Nenortas Collection)

~ Researched and written by Todd Jones, HPA Intern, September 2010

Cogswell Hall ~ American School for the Deaf

More about Cogswell Hall~ Researched by Mary A. Falvey, HPA Senior Program Assistant, September 2010

State Street

More about State StreetWhat we now call the Old State House was finished in 1796, and designed by Charles Bulfinch, who also designed the Massachusetts State House and contributed to the design of the U.S. Capitol. The lot had been the location of multiple meeting houses since 1636. From the time Connecticut was working on its new capitol in 1878, until the Hartford Municipal Building opened in 1915, the structure served as City Hall, and was unusually painted according to the Mayor’s favorite colors. Numerous important events occurred in the historic building, including the Amistad trials and the notorious Hartford Convention during the War of 1812, when the New England states contemplated secession.

In 1883, the federal government opened a large Post Office building on the east lawn adjacent the Old State House, visible in the photo. It was a grand building in the wrong location; too close to the Old State House, which blocked the eastern views. When the Post Office sought to expand at the turn of the century, the federal government actually contemplated demolishing the Old State House for the necessary room. In 1934, this unruly neighbor that never quite fit finally met the wrecking ball itself. The long Colonial building on the left was the United States Hotel, a premier accommodation in the city since at least the early nineteenth century. The old Honiss’s Oyster House first opened in that building in 1845. The hotel, though, was demolished only a few years after this picture was taken, making room for the Hartford Federal Savings Building. That historic Beaux-Arts building actually still survives, as it was incorporated into the modern State House Square complex in the mid-1980s.

The Greek revival building next to the hotel was the Hartford Bank, built in 1834; and the next structure along State Street was the old Hartford Courant building. By the 1950s, both had long been removed to make way for newer buildings, which included a W.T. Grant department store, the Federal Bakery, and two theaters. Coupled with newsstands and frequent foot traffic, the State Street of the mid-twentieth century was a very busy and vibrant place.

Through the center of the photograph, one can follow State Street all the way down to the Connecticut River. Along either side of the street, buildings housed cafes, tobacco exchanges, and stores. An old steam river boat, the Capitol City, made regular trips between New York City and Hartford, making its final run in 1931. Before dykes and highways barricaded the city and its river, the waterway played an integral role in the life of Hartford, which in fact really was a major port city. The commercial center of the city stood around the Old State House, while trade centered on the river: State Street connected the two, and made Hartford what it is today. (Photo: R.S. DeLamater, Courtesy of the Tomas J. Nenortas Collection)

~ Researched and written by Todd Jones, HPA Intern, August 2010

Charles R. Forrest House (1045 Asylum Avenue)

More about the Forrest HouseBorn in 1842, Charles Robert Forrest first arrived in Hartford in 1879. Through the years, as a director of the Connecticut River Lumber Company, American Typefunders, Sponsel Rapid Fire Gun Company, and other businesses, Forrest became a substantially wealthy citizen of the city. It also did not hurt that his wife was the daughter of one of the state’s richest men, William H. Chandler, and inherited a hefty fortune upon her father’s death in 1888.

Typical of rich Victorian Era gentlemen, Forrest was a member of many high-end organizations, such as both the University and Yale Clubs in New York City, the Hartford Club, and the Republican Club. Also typical of the wealthy, Forrest sought to show off his financial success by building an extremely large residence, which he did in 1891 at 1045 Asylum Avenue.

The beautiful stone work, as seen in the grand porch and first floor, was built by famous Hartford contractor John R. Hills, who also worked on the Mark Twain house on Farmington Avenue twenty years prior, and was a popular builder for many other wealthy city residents. The home also had wonderful wood work and a well-manicured lawn with stately trees.

The home combined many elements from assorted architectural styles. From one vantage point it had the symmetry of a Colonial revival, and from another it had the turrets and romantic unpredictability of a Queen Ann. Dormer windows on the third level even had Tudor-like windows. A number of exterior porches allowed for wonderful views from almost every side of the residence.

On October 6, 1912, Charles Forrest died, and left his estate to his wife. Forrest’s entire wealth was estimated at about $330,000, equivalent to over $7.3 million dollars today. When his wife, Harriet, died almost ten years later, the Asylum Avenue home was valued at $70,000, equal to over $800,000 in modern dollars. After 1949, when the last Forrest daughter died, the house was put up for sale and soon demolished to make room for modern structures. At the time, the character of Asylum Avenue near Woodland Street was transforming dramatically as commercial buildings and apartment houses replaced the old palatial mansions.

Keney Memorial Tower

More about Keney MemorialThe trustees whom Henry entrusted his wishes ultimately decided to make a clock tower on the site of the old Keney homestead and store. However, they decided not to dedicate the memorial to the business, as Henry had originally intended, but instead to the brothers’ mother. Evidently the trustees felt this would be a little more appropriate. Many claim that the tower currently stands as the only known monument built to a woman solely for being a good mother.

Completed in 1898, the Keney Memorial Tower stands 130 feet tall at the corner of Main Street and Ely Street, where Main Street and Albany Avenue merge, in an area known as Tunnel Square. It has since become a gateway for the Upper Albany and Clay Arsenal neighborhoods. Made of brownstone, it is Hartford’s only completely free-standing tower, architecturally unique not only in Connecticut but in all of New England. Clean, straight lines accentuate the Victorian structure’s tall stature, and four gargoyles perched at the top complete its wonderful Gothic design, completed by New York architect Charles C. Haight. Inspired by the Tour Saint Jacques in Paris, it brings a little flavor of the City of Lights to Hartford.

On May 2, 1899, the clock, which had been installed the previous winter by the Seth Thomas Clock Company from Thomaston, and the chimes, built by the Methuen Bell Company from Massachusetts, first started to keep time for residents of “the Tunnel,” the area around the tower. For almost fifty years, starting in 1899, local watchmaker Charles W. Neal was in charge of keeping the clock, 65 feet above street level, in working order. Every eight days he would climb the 79 steps to the clock mechanism and wind the 14-inch crank to keep the hands of the four 8-inch diameter clocks moving. He estimated that by the 1940s he had turned the crank at least a total of 1,564,160 times.

In the early 1990s, the Tower received a much-needed restoration, which took over a year and cost nearly $200,000. Broken windows were replaced, the surrounding fence was repaired, and graffiti was erased- all to make the monument a more appealing gateway. A new computerized chime scheme was installed as well, which could play a larger range of tunes, though the original mechanism remains. To put in the new technology, though, over a foot of pigeon droppings had to be removed, which had formed over the decades on the structure’s top floor and blocked a rarely-used access hatch to the original bells.

A symbol of Hartford’s Gilded Age, a testament to motherhood, and a beacon that can make locals old and young smile, the Keney Memorial Tower has now stood for well over one hundred years. It is appropriately listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and is a perfect example of Hartford’s existing diversity of unique architectural structures.

~ Researched by Todd Jones, HPA Intern, August 2010

~ Photograph: A. Wittemann, circa 1903

Goodwin Castle – 83 Woodland Street

More about Goodwin CastleIn 1871, construction began on what would become not only the largest private residence in Hartford, but in all of Connecticut during an age when displaying wealth and Victorian prestige were in full vogue for those with means. As a prominent businessman and banker from a wealthy city family, James J. Goodwin built this new home at the corner of Woodland Street and Asylum Avenue at a cost of more than four times what nearby neighbor Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) paid for his comparatively petite home around the same time.

Eventually known as the Goodwin Castle, the home had a Gothic exterior made of granite. A massive, imposing tower drew the attention of all who traveled up the tree-lined driveway, while a series of smaller gables and spires made the structure look more appropriate for the European countryside rather than Hartford’s Asylum Hill neighborhood. At 275 feet in length, the castle was longer than the State Capitol dome is high, and dwarfed even the finest of West End homes.

The castle’s interior fully evoked the popular Victorian style of the day. The exquisite parlor contained woodwork of pale maple and ebony, with a massive chandelier hanging from the decorated ceiling, and a large mirror mounted over an equally great mantel. Furnishings fit for a king, or at least Hartford’s financial equivalent, filled the room and house to an expected level of Victorian excess.

Upon Mr. Goodwin’s death in 1915, his entire estate had a value of $30 million dollars, or over $600 million when adjusted to modern levels of inflation. His wife continued to live in the castle until her death in the late 1930s, after which Aetna acquired the home and its eight acres of property.

By May 1940, demolition of the structure commenced, and an office building eventually took shape on the site. The New York and Hartford House Wrecking Company took on the massive job of tearing down the granite castle, which took more than double the time that normal-sized residences required for destruction. Before the home’s demise, though, the Goodwin family donated most of the furnishings from the grand parlor to the Wadsworth Atheneum, and the museum has continually displayed the pieces in a reconstructed parlor room exhibit. On a yearly basis, period Christmas decorations are even taken out to adorn the Goodwin Parlor for the holiday season.

~ Researched by Todd Jones, HPA Intern, June 2010

~ Photographs courtesy of Tomas J. Nenortas Private Collection.

To learn more about Goodwin Castle and the architecture of the Goodwin family, see Philip Lippincott Goodwin’s Rooftrees or The Architectural History of an American Family (Philadelphia: F. B. Lippincott Company, 1933)

The Linden

More about The LindenIn 1891, Frederick Savage Newman designed The Linden, which would eventually occupy an entire block of Main Street in SoDo (south Downtown), between Linden Place and Capitol Avenue. Frank Brown and James Thomson, who owned a company that operated out of the Cheney Building, hired Newman, and his plans echoed the style of H.H. Richardson’s iconic block which sat farther north on Main Street.

As one of Hartford’s first large apartment buildings, The Linden attracted many young professionals seeking a level of luxury downtown. Early on, tenants even enjoyed limited housekeeping services. A January 23, 1892 article in the Hartford Courant described The Linden as “a model apartment house,” adding that “the rooms are large enough for comfort, and are small enough to look cozy and be easily furnished.”

Each room enjoyed hot running water, gas fixtures, and with an eye to the future, even the ability to easily install electrical devices. A novel mail chute also allowed tenants to simply drop a letter through a slot on any floor, and see it easily arrive down at the main hall for delivery. The building also advertised a speedy elevator, and had interior wood work made of cherry birch. A later owner of the property drilled a private artesian well to provide water for the building and maintained an ice house on the premises.

The exterior façade of the building still contains quarry-faced brownstone, red sandstone, brick, and arches which surround separate bays of three windows. Far atop the structure’s corner with Main St. and Linden Place stands its most recognizable architectural feature. The circular parapet, capped by a copper roof, nicely compliments the similar tower of the earlier Hotel Capitol down the street, as well as the spires of Main Street’s churches. As part of Newman’s original design, spaces for storefronts also line the street-level first floor.

By the 1970s, The Linden had fallen into relatively poor shape, and just like the case with so many other Hartford buildings, talk of its possible demolition spread. Under new ownership, though, the structure enjoyed a major rehabilitation and remodeling during the 1980s, and started to return back to its glory days as a luxury apartment complex. At the same time, The Linden was also included within the newly designated Buckingham Square Historic District, on the National Register of Historic Places.

As concerned stewards of this unique building, The Linden Homeowners Association recently completed major maintenance on the exterior, including repointing of the exterior brick and stonework.

~researched by Todd Jones, HPA Intern, June 2010

~ photo Geer’s Hartford City Directory, 1913 courtesy of the Tomas J. Nenortas Collection

Seyms Street Jail

More about Seyms Street JailDesigned by famed city architect George Keller, the intimidating Seyms Street Jail, with its magnificent red brick exterior, granite columns, and gables, stood like a castle in the Clay Arsenal neighborhood from 1873 to 1978. First known as the Hartford County Jail, the state considered the structure obsolete by 1978 after the construction of new facilities in the North Meadows. After demolition, the city created Julio Lozada Park on the site.

Upon its completion in 1873, the Hartford County Jail stood like a castle in Hartford’s Clay Arsenal neighborhood. Eventually renamed the Seyms Street Jail after the city road it lined, the structure consisted of a magnificent red brick exterior, granite columns, and gables. The Yale Lock Company of Connecticut provided over 200 locks for cell doors.

George Keller, Hartford’s famous architect, designed the structure. He admitted to a lack of knowledge regarding prisons, so he traveled throughout the country in order to view other modern penitentiary designs to create a building in Hartford that was both aesthetically pleasing, and fully practical and functional for its intended use. A number of additions and changes were made over the next century, but Keller’s basic designs still very much characterized the jail.

Legend had it that nobody ever escaped from the prison, and it had a notorious reputation as a place of misery. In May of 1977, two inmates committed suicide in the jail, and a number of citizens later demonstrated outside to protest the wretched conditions of the prison. In a letter-to-the-editor printed in the Hartford Courant a month later, a former prisoner from Rockville said the Seyms Street Jail was “nothing but a hell-hole.”

Yet, by the summer of 1977, a new jail had been dedicated by Gov. Ella Grasso in Hartford’s North Meadows, which effectively ended the need for the century old prison on Seyms Street. Soon after, all 350 prisoners were transferred to the modern jail, being moved 12 at a time in handcuffed groups. The process took 10 hours, and left the Seyms Street Jail abandoned.

The State ignored the structure which it considered unnecessary and obsolete, and did nothing to stop the numerous acts of vandalism and arson which plagued the building. Before its ultimate demolition, photojournalist Carolyn Carlson chronicled some of the interesting graffiti that could be found on the jail’s old walls. In an article printed in the Hartford Courant a year later on July 15, 1979, Ms. Carlson described the text and drawings created by the desperate and depressed occupants of the Seyms Street Jail.

There were names, such as “Steven the Greek” and “the Rebel from Florida;” and town names from all over Hartford County. A number of crude drawings depicted quaint wood cabins, skulls, and drug paraphernalia. Like a gunslinger from the old West who carved notches on his gun, many prisoners proudly listed their crimes on the walls. And of course, there were others who wrote “I am being convicted of a crime that I did not do.” Prisoners also used a number of methods to keep track of time, such as calendars. One prisoner summed it all up well: “Each day here is a living death.”

By the summer 1978, the old jail and all its history was torn down after sitting dormant and lonely for a year, and the property was turned over to the city. The Mayor sought to use the land for a new police station or housing, while the Council and neighborhood, whose plans were ultimately realized, wanted to see the land turned into a park to honor Julio Lozada, a local 12 year old who had tragically died nearby.

~ Article researched by Todd Jones, HPA Intern, May 2010

Conn. Mutual Life – Main & Pearl Streets

More about CT Mutual LifeThirty years later at the turn of the century, the building underwent a major remodeling under the guidance of architect Ernest Flagg. A massive new addition along the structure’s Pearl Street front doubled its available floor space, and two additional stories were added to the original structure, with a mansard roof replacing the previously intricate top. In addition, the classical statues above the front entrance were removed, and according to legend, buried somewhere in East Hartford to await future treasure hunters. The updated and expanded structure also left much space to be rented out, and as the largest business building of its kind between New York and Boston, it became a center of commerce.[1]

In 1928, the Hartford National Bank and Trust Company bought the building and moved their headquarters there from a smaller structure at the corner of Main and Asylum Streets. Before moving in, the Bank remodeled the structure, fundamentally changing the first and second floors, and creating over half an acre of available interior space. According to the Hartford Courant, the Bank reopened the structure amidst much fanfare and celebration, with visitors from all over the northeast being “personally escorted by young women through the various departments.”[2]

Created by the modifications to the first two floors, a grand and glamorous main banking room greeted all who walked through the front doors. A large walnut sign noted the Bank’s original founding in 1792, and the counters could fit up to twenty tellers. Pillars of Tennessee marble stretched to a high ceiling covered with decorations inspired by foreign coins and currency, all gilded in gold.[3]

By the early 1960s, though, the Bank decided that the magnificent old building no longer properly fit their needs. In 1963, the 1870 half of the building on the corner of Main and Pearl was demolished, with the groundbreaking for a new structure taking place on April 21, 1963. By 1967, a modern 26 story office complex opened for business on the site.

~ Article researched by Todd Jones, HPA Intern, May 2010

[1] “Connecticut Mutual,” Hartford Courant, April 7, 1900, 8. [2],[3] “Bank Starts Business in New Building,” Hartford Courant, December 18, 1928, 27.A. C. Hine – 189 Washington Street

More about CT Mutual LifeMiner Garage – 164 Allyn Street (corner of High)

More about Miner GarageThe Miner Garage Company at the southeast corner of Allyn & High Streets (164 Allyn) was the result of one man’s vision for the future of the automobile industry and is believed to be the first building in Hartford designed solely for the repair, sales and storage of automobiles. The garage was built by Henry C. Judd and rented back to his former bookkeeper Samuel A. Miner.

Miner was enamored with automobiles from his first purchase of a steam powered Prescott surrey. He left his job as a bookkeeper for H. C. Judd & Root in 1902 and struck out on his own, hoping to sell 3 car s a year and do some repair work. He estimated that he had sold approximately 300 vehicles by the time he began renting this garage that was built for him by his old employer.

With a few exceptions, automobile dealerships function today much as Mr. Miner’s did 100 years ago (albeit on larger tracts of land). The large plate glass windows at the corner of the building were for the display of the latest car models for sale. The two large doors, center and right, were for the cars to enter and exit into the service bays. Separate waiting rooms were provided for ladies and gentlemen.

An important function of these early garages was the storage of automobiles. Car owners who did not have carriage barns on their property needed a place to store their vehicles. Before the advent of individual garages or “car sheds,” city residents would leave their automobiles at the garage where it would be stored as well as repaired, washed and in the case of the early electric vehicles, recharged.

– Researched by Mary A. Falvey

Deerfield Avenue

More about Deerfield AvenueThis postcard of 1-3 Deerfield Avenue in the Upper Albany neighborhood gives us a rare view of one of the two original deer that graced that entrance of the street at Albany Avenue. This late Queen Anne two-family home was built by the Nevels Brothers., who developed this street and Oakland Terrace. The spindle-work detailing on the porches is a signature feature of the Nevels Brothers work at the beginning of the 20th century.

The handsome home at 1-3 Deerfield Avenue in the Upper Albany neighborhood was built in 1903 by the Nevels Brothers and purchased by James G. Buckley who at the time was the assistant secretary of the Hartford Foundry Corporation on Windsor Avenue. Based on the date and message on the postcard, the family in this scene is most likely that of Henry and Mildred (“Millie”) Wilkinson. Mr. Wilkinson was a steam boiler engineer who joined the Travelers Insurance Company on April 1, 1907 as an inspector.

The homes on Deerfield Avenue, along with those on Greenfield Avenue and Oakland Terrace, were built by Michael J. and Thomas J. Nevels of Nevels Brothers. The Nevels, along with their brother Andrew and later another brother Anthony, arrived in Hartford in 1897 from the Deerfield, MA area (hence their naming of this street Deerfield Avenue). They built houses on Jefferson and Sargeant Streets before joining other land developers who were converting the open fields in the north and south sections of Hartford. The layout for Deerfield Avenue was filed in the Town Clerk’s office on August 26, 1901.

The development of Deerfield Avenue illustrates a notable change in the way neighborhoods were constructed. Starting from around the time just prior to the Civil War, “developers” would purchase large pieces of land and divide them into individual lots and streets. Individual lots would then be sold and developed. Several lots might be purchased by one builder but the entire street would not be developed as a whole by any one builder.

With the advent of mass produced building materials and available financing, individual building firms began constructing “on spec” and selling directly to individuals. These homes were marketed to the growing middle class population of clerks, foremen and small business owners who took advantage of home building and loan societies for mortgages. The expansion of the electric streetcar system into Upper Albany provided affordable transportation and advanced the rapid growth of the neighborhood. Hence we have the beginnings of a cohesive subdivision.

The actual architect for the Nevels Brothers houses has not been identified. In all likelihood, they would have used some of the many plans available through builder catalogs and architectural plan books.

THE DEER STATUE

More about The Deer StatueDuring the social unrest in the 1960s, the deer were vandalized and toppled. One was taken into storage by the City of Hartford and subsequently lost. Its mate was rescued by a local professional who took it home and stored it in his garage. The Deerfield/Greenfield block club spearheaded the effort that resulted in the statue being restored by New Hartford artist Michael Sidd and returned to its home in November, 1980.

Unfortunately, this statue was vandalized within a few years. As part of its plan to revitalize Deerfield Avenue, the Christian Activities Council commissioned artist Karen Petersen to sculpt a new deer which was installed in October of 2006.

To read more about the development of the North End at the beginning of the 20th century, see the June 5, 1907 Hartford Courant Articles “Open Country Building Up” and “Men Who Improve Real Estate.”

~ Researched by Mary A. Falvey, with contributions by Sam Diters,

HPA Intern and Tomas J. Nenortas, March 2010

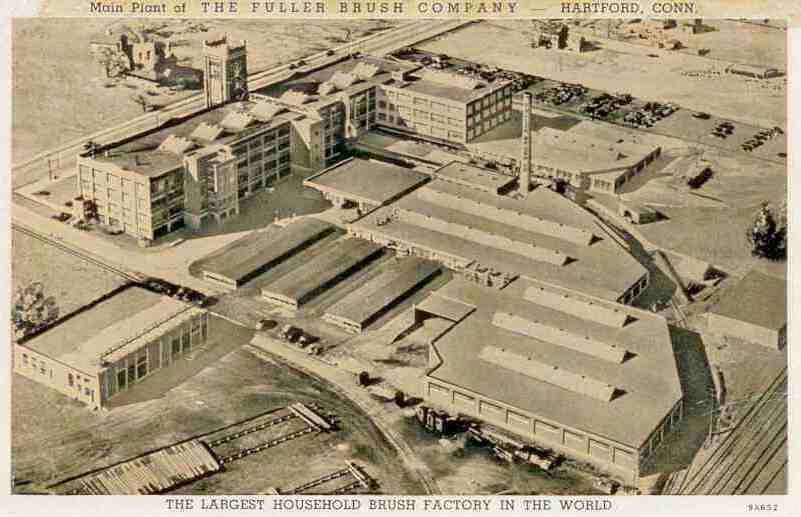

Fuller Brush

More about Fuller BrushThe Fuller Brush Company, founded by Alfred Fuller, moved to their new factory at 3580 Main Street in 1922. The factory was designed by Buck & Sheldon, Inc. and constructed by the Brent-Bartlett Company. The Fuller Brush company made a name for itself manufacturing the highest quality brushes and cleaning products. The company is best known for its door to door salesmen aptly titled, “The Fuller Brush Man.” This sales tactic was originated by Alfred Fuller himself, and the salesmen became a welcome sight for homeowners across America. In 1972, following years of profitable work and growth, the brush company relocated to Kansas where it remains today.

Since the early 1900’s the Fuller Brush Company has provided homes across America with high quality brushes and housekeeping goods. The company began as one man’s door-to-door sales business in Somerville, Massachusetts, started by Alfred Fuller. He spent three years as a salesman near Boston selling low quality brushes to housewives. Fuller knew that to meet success he needed to find a way to produce more convincing products. After building a machine that produced higher quality brushes that in various forms, he once again set out door-to-door and met with considerable success. With this new market and a machine capable of making many brushes in one day, Fuller’s business was ready to expand. The work space was too small for his growing ambitions so he prepared to relocate. Hartford, being a bustling industrial center, was the perfect location for Alfred Fuller to begin the Fuller Brush Company. Fuller opened his main factory at 3580 Main Street in 1922 and the business quickly found a market providing brushes and cleaning goods to homes in Hartford and the surrounding area. The Factory itself was designed by Buck & Sheldon, Inc. and was constructed by the Brent-Bartlett Company. The Factory, like many of its contemporaries, was built as a visual symbol of Fuller’s corporate enterprise with an impressive Gothic-style brick tower adorned with pinnacles and battlements rising high above the city street.

Fuller’s company is best known for their door-to-door salesmen who traveled to houses in the region advertising and selling Fuller brushes. During the mid-1900’s the “Fuller Brush Man,” became an American Icon for their quality goods and the trademark character of their door-to-door salesmen. The Fuller Brush Company revolutionized the nature of housekeeping goods and spawned a vast market in which Fuller’s company prospered. By the time of Alfred Fuller’s death in 1973 the company had relocated to Great Bend, Kansas, where it resides to this day selling house care products to customers across the globe.

~ Researched by HPA Intern Sam Diters, February 2010

Pratt & Whitney

More about Pratt & WhitneyThe Pratt and Whitney Company was founded in 1860 by Amos Whitney and Francis Pratt, two aspiring and talented mechanical engineers who believed that in the coming era a higher degree of precision and interchangeability would be needed in manufacturing mechanical parts. Both Amos Whitney and Francis Pratt found jobs at a young age working at Colt’s Armory producing firearms, where the men met and began a long lasting relationship in the manufacturing business. From the start, the two young men spent their time committed to decreasing error size and elevating the precision of their machines. In the company’s early days the two founders worked on their own out of a small rented room on Potter Street working with only a few tools and little help. Pratt and Whitney’s first significant accomplishment was their building of the Automatic Silk Winder, which was done so well that the Pratt and Whitney name quickly began to spread around the metal working industry. After a few years of hard work and perseverance the men were able to rent out one floor of the Weed Sewing Machine Factory to continue their work. At this time, during and after the Civil War, the company did a substantial amount of work for Colt’s Armory producing guns and the necessary machinery needed to produce them. This work continued for several years with the company accepting contracts from various suitors, manufacturing guns, tools and machinery for countries all over the globe. With the company’s success more factory space was needed and following the bankruptcy of the Pope Manufacturing Company, formerly Weed Sewing Machine, Pratt and Whitney expanded to occupy the entire property at 1 Flower Street. Pratt and Whitney expanded the factory, building a Small Tools department and other manufacturing additions. Pratt and Whitney’s work in firearms lead to their interest in interchangeable parts, an idea they helped pioneer and one that would revolutionize the nature of mass production. For interchangeable parts to work a new standard in accurate gages and precise measurement was needed, luckily this was Pratt and Whitney’s expertise. The result of this expertise was the Pratt and Whitney Standard Measuring Machine, a machine that allowed unheard of precision in measurements and manufacturing. For the next decade and into the early 1900s the company flourished, even with both of its founders retired by 1902. The company continued to produce machinery and precision tools but soon discovered its true potential in the field of aviation. The company’s accuracy and precise measurements made them a perfect candidate for the pioneering of the early aviation industry. After partnering with Frederick Rentschler, an aviation engineer in 1925, Pratt and Whitney began to focus on aviation with the completion of their R-1340 Wasp engine, which powered the planes of Amelia Earhart, Wiley Post and many others in the early days of aviation. Today Pratt & Whitney’s headquarters can be found in East Hartford and the company continues to produce civilian and military plane engines, powering over 40% of the worlds commercial aircraft. (1)

[1] “Accuracy for Seventy Years 1860-1930” Pratt and Whitney, 2003. www.prattandwhitney.com~ Researched by Sam Diters, HPA Intern, February 2010

Weed Sewing Machine

More about Weed Sewing MachinelThe invention of the Sewing Machine was an important stepping stone in the advancement of mass production, along with Colt Firearms and Pratt & Whitney, Weeds Sewing Machine Company helped streamline factory work and opened jobs for thousands in and around Hartford in the late nineteenth century. By 1870, the Weed Company had incorporated itself as a mass manufacturer of Sewing machines and was widely known for its craftsmanship and productivity. Along with the Colt Armory, the Weed Sewing Machine Company launched Hartford into being one of the largest industrial centers in America.

In 1878 the nature of the Weed Sewing Machine Company changed drastically. Albert Pope, an Industrialist from Boston, was fascinated with the, “Penny Farthing,” bicycles from Europe that featured a large front wheel and a small rear tire. Pope believed these bicycles could be a substantial commercial success in America, and would be a huge advance in public transportation. Pope knew that people had grown weary of being restricted to the rail road for transportation, with its set paths and rigid schedule, and sought a form of transportation that would allow for greater individual freedom when traveling. Pope knew that with the proper marketing and a suitable manufacturing plant the bicycle would be a success. In his search for a manufacturer, Pope set his eyes on the Weed Factory for its large size and excess of working machines. Pope quickly gained the favor of the Factories superintendent, George Fairfield, and Fairfield, while not totally convinced of Pope’s proposition, nevertheless accepted an order of 50 bikes. From there began two decades of hard work and cooperation between Pope and Weed on manufacturing the Bicycle. The early models created at the Weed Factory were named the, “Columbia,” a name which rings familiar for many who enjoyed a ride on a Columbia bike in their childhood. This bicycle was inflicted with various safety hazards presented by the over sized front wheel and often caused unfortunate riders to be launched over the handlebars and onto their heads. These hazards prompted Pope to create a safety version that was more marketable and closely resembles the bikes seen today. In 1891, after the collapse of the sewing machine market, Pope merged the entirety of the Weed factory under his name, creating the Pope Manufacturing Company. Alongside bicycles, Pope began work on an “electric carriage,” years before Henry Ford would announce his Model T in 1907. Pope’s automobile designs went through a number of different stages, with each model more efficient than the last, however Pope could not win the battle over the industry as Ford’s Model T won the hearts and minds of the American people. Pope’s factory continued to be in use until the mid 1900s and contributed greatly to the relative economic security that could be seen in Hartford during its tenure, at many times being the largest employer in the city with over 4,000 employees.

~ Researched by Sam Diters, HPA Intern, February 2010